This is a story about how I used Paliscope YOSE™ to analyze evidence and prepare reports for the most important prosecutorial case of my 32-year law enforcement career.

The Story

Amanda Michelle Todd was 15-years old when she took her own life. She had been the victim of constant harassment, bullying and sextortion for a few years prior by an unrelenting tormentor. Her victimization started in 2009-2010 when she was in the 7th grade. During an online video chat, a stranger convinced her to show her bare breasts on webcam and he recorded it. He then distributed those images all over the Internet.

This exploitation set off a chain of events for Amanda, leading to depression, anxiety, self-harm, substance abuse and trouble with her school grades. She could not escape the sextortion as the perpetrator would continually create fake personas and stalk her. Even when she moved and changed schools, he found a way to continue the harassment and threats.

On September 7th, 2012, Amanda posted a 9-minute video on YouTube, where she told her story using a series of flash cards. The video went viral but not until she died by suicide on October 10th, 2012.

In January 2014, a United Kingdom investigation into some Facebook activities led to the arrest of a Dutch citizen named Aydin COBAN. An examination of his computer revealed over 5,000 names of people on social media that he had been sextorting. In April 2014, he was charged with over 70 offences relating to almost 40 victims all over the world. That same month, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) charged him with offences relating to the Amanda Todd case. COBAN was convicted of the Dutch offences in March 2017, and he was sentenced to over 10 years in prison.

In December 2020, COBAN was extradited to Canada to face the prosecution for his sextortion of Amanda.

You can read more on her story at this link.

The Beginning

My involvement in this prosecution came back in October 2020. I was contacted by the lead prosecutor in the case. She had been provided my contact details in Australia by a former RCMP member. She explained she was responsible for a high-profile case involving voluminous Facebook data and reports. At that time, I was not aware of which case she was referring to.

We discussed Facebook records and their data as well as how this type of evidence can be presented in a trial. She was aware of my previous experience in doing exactly that. While I was with the Toronto Police Service, I had been qualified as an expert in 4 previous cases with respect to the operation of Facebook, the social network, as well as in the Facebook records and data. In those cases, I had analysed and testified to thousands of Facebook artefacts and how to interpret them from the Facebook records disclosed to police. The prosecutor was extremely interested in what I could do for their case.

We agreed to proceed with providing me a sample of their evidence (a Facebook record), but without any context or facts about the case. This allowed me to objectively comment on the record and its contents without knowing which artefacts were pertinent to the prosecution. In the paragraphs to follow, I will describe the steps taken, the role or methodology used and show some excerpts from the case to highlight the analysis I had conducted as well as how I eventually presented that evidence.

I received a 34-page Facebook record in PDF format from the prosecutor. I recognized it immediately and it contained all of the information I was expecting to see. As a bonus, it was a 2013 record and it covered a time period for account activities between 2010 – 2013, the very same years of my specific expertise and previous case testimonies. I know these records very well. A record such as this is what Facebook discloses to law enforcement when they are served with the appropriate legal request, court order or search warrant, depending on the authority. It is a report about a user account, but generated for use as a “business record” for law enforcement or investigative purposes. It is not the raw data from Facebook, but it contains artefacts extracted from the account in question.

For example, the following data may be found within this record:

- Account number

- Dates for the relevant data

- Date of the report

- Account name

- Registered email addresses

- Vanity name also known as a “username”

- Date of birth

- Registration date

- Registered phone numbers

- Recent session activities (account logs for access) with timestamps

- Notification settings

- Privacy settings

- Friend requests

- Messages (sent and received) with timestamps

I did not know what charges had been laid or what the actual investigation was about until I saw the messages in the record. I knew then, this was about Amanda Todd. The important part was I did not allow that to distract me from offering some facts, some opinion, or some observations from an objective and impartial viewpoint, because that is the role of an expert witness.

I anticipated that because the content of the messages themselves, speak on their own, it was likely that the activity logs of where, when, and how the account was accessed was important. It has been always a challenge with Internet facilitated accounts to “prove or establish” who was behind them. We call it “putting someone at the keyboard.” I have testified in great detail about these session logs in every case.

I concentrated my analysis on what these logs, as seen in this specific record, could say about the potential user of this account. For a variety of reasons, Facebook records a user’s account activity when they login and when they logout. They also note any activities or changes to sessions in between while the account is in use. These are entered into the session activities log. The entries include network information called HTTP headers transmitted by your device, such as your IP address, device identifiers also known as “user agent data” and cookies as well as the associated date/timestamp for each one. Facebook uses this data to verify, track and maintain who and what is accessing their network. There are a number of account security options users can enable because of these artefacts stored in their account.

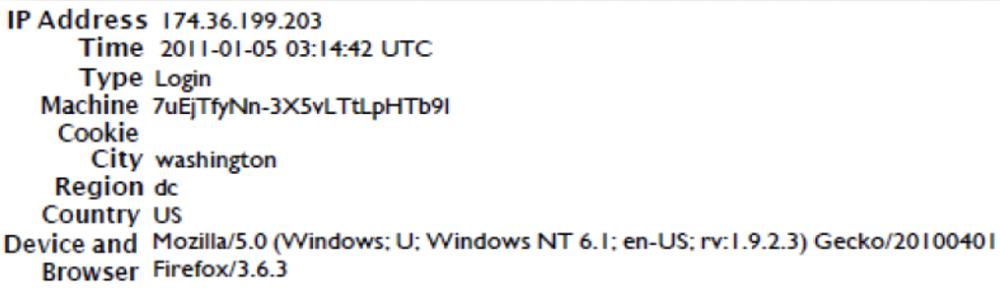

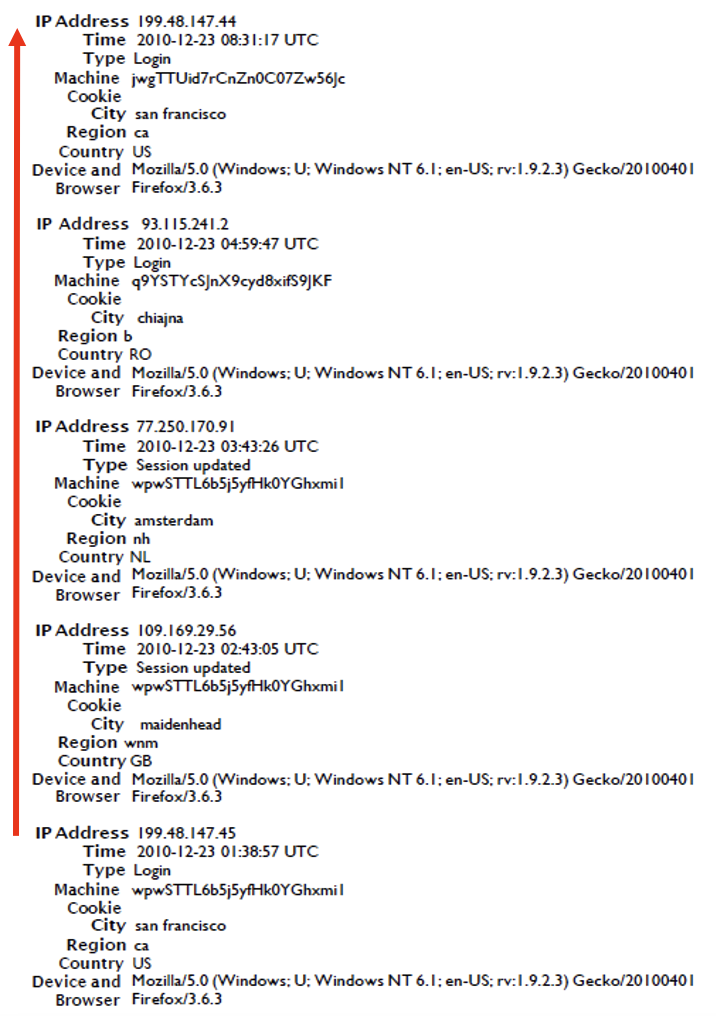

Let us take a look at one of these session entries from the record itself:

- As mentioned above, Facebook logs your IP address and the date and time of the account activity in this case the user has logged in.

- The “machine cookie” value is a proprietary process Facebook uses to determine that the user has logged in from a specific browser. This is one of many cookies Facebook places on a user’s device.

- The City, Region and Country is how Facebook has geolocated the IP Address above

- The device and browser or user agent data is encoded

- When decoded, the device used here had a Microsoft Windows 7 operating system and the Internet Browser was Mozilla Firefox version 3.6

The machine cookie, when unchanged, can tell us if an account has been accessed from the same device using the same browser. This is true even if the account is logged out or is accessed from a different IP address on a different date and time. If the user deletes the cookies associated to Facebook from their browser, or uses the same device but a different browser, a different cookie value would be seen in the account records.

The Facebook session activities are shown in the record chronologically and typically in descending order from newest to oldest in time.

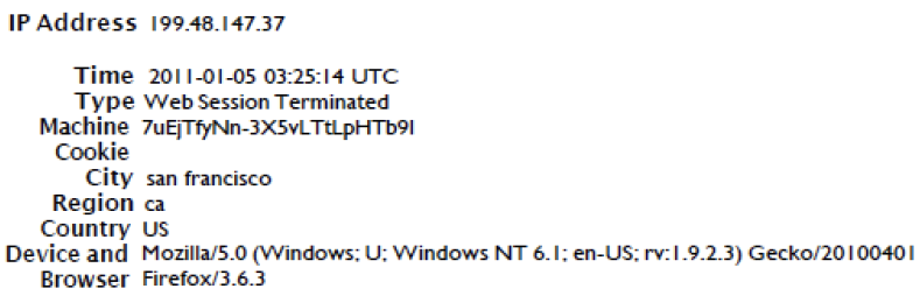

The very next entry within this record is this one:

What did my analysis about these two entries say?

- On January 5th, 2011, at 03:14:42 UTC

- The account was logged into from a device using IP address 174.36.199.203

- The IP address geolocates to Washington, DC, USA

- The device had a Facebook Machine cookie ID of 7uEjTfyNn-3X5vLTtLpHTb9l

- The device was using Microsoft Windows 7 operating system and the Browser was Mozilla Firefox version 3.6

- On January 5th, 2011, at 03:25:14 UTC

- The account was logged out (Web Session Terminated) from a device using IP address 199.48.147.37

- The IP address geolocates to San Francisco, CA, USA

- The account was logged in for 10 minutes and 32 seconds

- The log out was from the same device as the login according to Facebook because:

- The same Facebook Machine cookie ID of 7uEjTfyNn-3X5vLTtLpHTb9l was recorded

- The same device information of Microsoft Windows 7 operating system and Browser Mozilla Firefox version 3.6, were recorded

It is not physically possibly to travel from Washington, District of Columbia (DC) to San Francisco, California in 10 minutes and 32 seconds. They are approx. 4,570 kilometres apart, so something for me to note.

I analyzed the remainder of the 37 session entries in this record, the date range for them was from December 3rd, 2010, to January 5th, 2011. During those 32 days of entries, I noted there were 20 unique cookie values and 22 unique IP addresses. This pattern is unusual for a normal user, certainly not typical of someone who uses the same device and the same browser from the same location to access their Facebook account.

The next set of entries demonstrates how and why I drew the conclusions I did.

The way to understand these entries is to start at the bottom and read up to the top.

My observations and plausible explanations to the prosecutor was that this pattern, seen in this record, was indicative of the user accessing the account from a virtual private network (VPN) or proxy service. This was based on the frequent changes in IP addresses, and 4 different countries as well as the lookups I had conducted. I also indicated that it was consistent with either the manual or automatic deletion of the Facebook cookies from the browser. There were multiple cookies values, no logouts recorded, and the user agent data showed the same device operating system and browser version in a span of 6 hours, 52 minutes, and 20 seconds.

I authored a 14-page report highlighting these observations and how I might testify about them. I sent that report to the prosecutor.

A short time later, I found myself becoming the Facebook expert needed in the Aydin COBAN prosecution.

The Tribulations of a Legal System

Certainly, in most countries, the length of time it takes to run a prosecution can be months or years before a decision is rendered. Along that journey there are a number of processes or smaller hearings that are undertaken to argue any legal issues from either side. Typically, the most common one is where the defence attempts to minimize, limit, or eliminate crucial evidence that the prosecution is relying on.

The COBAN case had no shortage of pre-trial hearings. In one example, the defence challenged the admissibility and reliability of the Facebook records. This formulated the basis for the first part of my expertise and evidence. I was provided and analyzed all of the Facebook records and prepared a report about them. The prosecution provided records from 2013, 2016 and 2018, just under 27,000 pages in PDF. There were a series of questions and tasks associated to the request that I needed to answer.

I drafted a detailed report (188 pages) about those records and the related inquiries for a pre-trial hearing. In November 2021, I was qualified and testified by video as a Facebook expert at that hearing. I gave evidence about the interpretation of the records and the meaning of data contained within them. The purpose was to establish that the records could be used and relied upon by the prosecution at trial.

Facebook Inc. (back then) and now Meta, does not provide evidence or testimony about their records or data in court proceedings. In fact, they are generally not cooperative in assisting in prosecutions at all. This has always been the case and is why people like me have to become experts in explaining their network. The Canadian legal system cannot compel U.S. based Facebook employees to testify.

My testimony was a few hours over the course of three days and ultimately the court allowed the Facebook records to be further examined and to be used at trial. This kickstarted the real preparations of this evidence over the next 7 months.

Preparing for the Trial and the Role of Paliscope YOSE

Between November 2021 and the trial in June 2022, I authored various reports numbering into a few hundred pages. There were all in response to prosecution requests to provide or present evidence to the jury in the trial. Many of these reports needed to explain how computers connect to the Internet, what are IP addresses, VPNs, proxies, and cookies. I also had to explain how each of them work because they were the key artefacts, I was concentrating my analysis on with respect to the Facebook records.

In addition, the reports had to discuss how Facebook worked, how it had evolved between 2010 and 2013 because that was the time period these activities occurred. I further discussed Facebook policies, such as data retention as well as privacy and where those policies impacted on what may or may not be seen in law enforcement business records.

The final and most important piece was my analysis into 13 Facebook accounts and their associated records. Each of these accounts, the prosecution alleged, participated in the offences committed against Amanda Todd in one way or another. My job was to find the commonalities or connections between those accounts using a variety of methods and present them to the jury. I would also be asked to add opinion evidence, where applicable, about any connected data or relationships between accounts.

This is where I brought in Paliscope YOSE. I had been involved in the development of YOSE since 2016 when it was conceptualized. I have been using it as a beta tester ever since. I am remarkably familiar with how YOSE works and have seen it grow in its capabilities. I knew I could process all of Facebook records because they were PDFs and YOSE does an excellent job rendering the text. I could have utilized the natural language processing to assist with indexing a lot of textual intelligence contained within those documents.

I also knew that it would allow me to isolate all of the photos within those records and be able to utilize a number of image recognition techniques. But that was not what I needed for this case. What I needed was the ability to isolate a certain set of artefacts, the session activities specifically, and analyze connections or similarities between them. This meant I needed to focus on hundreds of session activities between the 13 accounts.

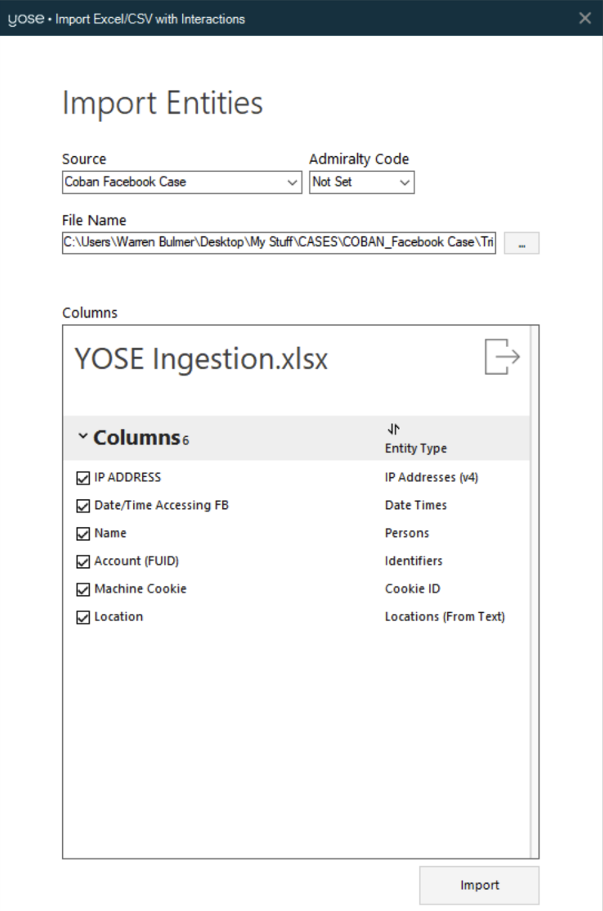

In the trial materials provided to me by the prosecutor, there was an Excel spreadsheet that they had prepared prior to bringing me on board. It was a part of their preparation of the evidence, and it contained a summary of just over 1,460 session activities from all of the accounts in question. The columns included IP addresses, dates and times, account names, machine cookie values, locations (derived from the City, Region, and Country) and some photo uploads. This was the answer as to how I was going to do my analysis. YOSE loves structured data, and it can import an Excel or CSV file.

I created a book for each account and the general contents for each book described any Facebook artefacts they had in common with the other targeted accounts in question. Wherever I found matching data, I outlined what the connections were. YOSE helped me find the connections, I then verified them in the Facebook records themselves and I used screenshots and Microsoft PowerPoint to present the evidence.

Presenting the Facebook Evidence & Connecting the Accounts

YOSE created an opportunity for me to visualize the data. One piece of information can be valuable, but when you can connect 2 or 3 pieces; it becomes powerful, and it can change the level of coincidence. There were 3 levels of data correlation that I drew attention to. The date and time was also a factor I used to show the proximity of the artefacts where it was important.

- Machine Cookie IDs in common

- IP Addresses in common

- Both IP Addresses and Machine Cookie IDs in common

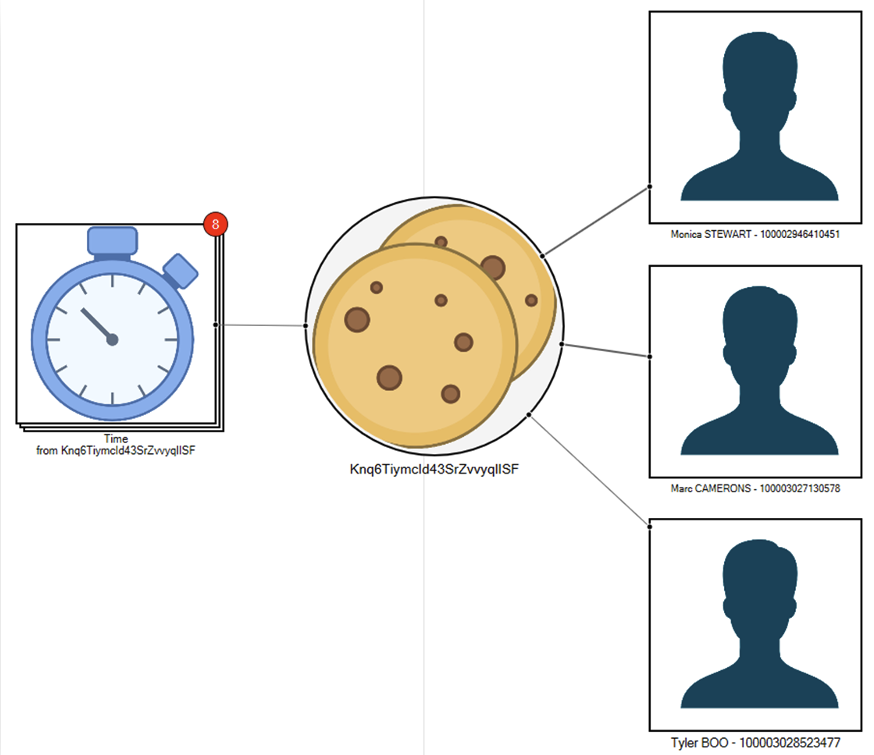

Machine Cookie Example:

This Machine Cookie ID was seen in the records for these 3 accounts and there were 8 different time/date stamps relating to those entries. Remember, a machine cookie is found on the device in the browser, meaning these users accessed their accounts from the same browser.

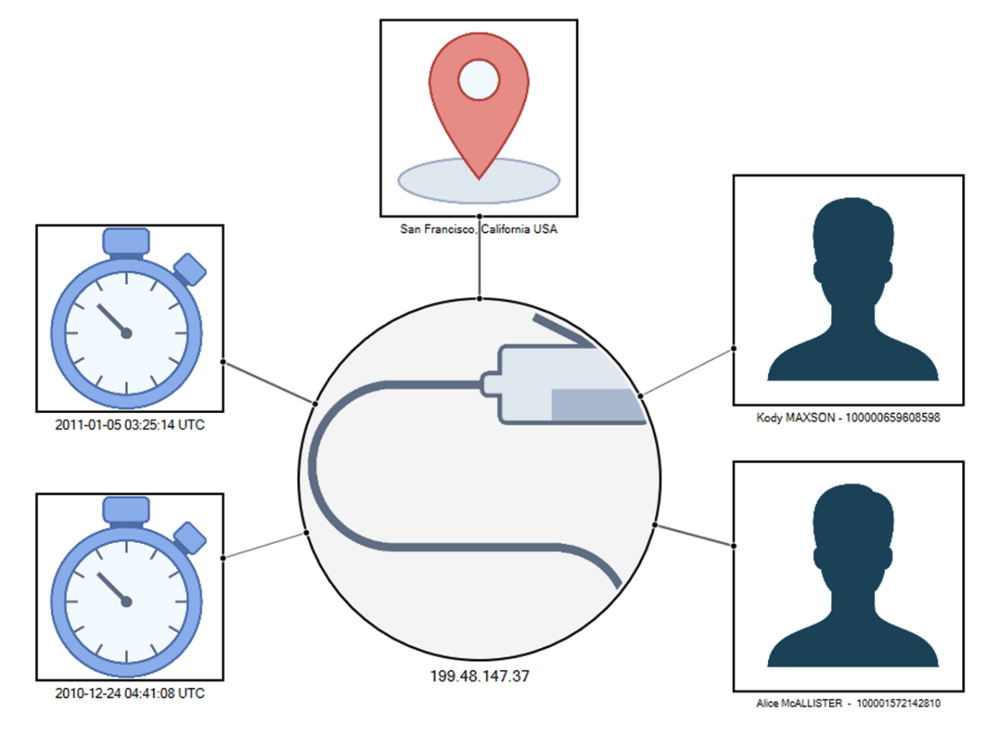

IP Address Example:

This IP Address was seen in the records for these 2 accounts and there were 2 different time/date stamps relating to those entries. Remember, an IP Address geolocates to a specific City, Region, and Country. It also means that these two users were using the same Internet Service Provider, VPN, or proxy server.

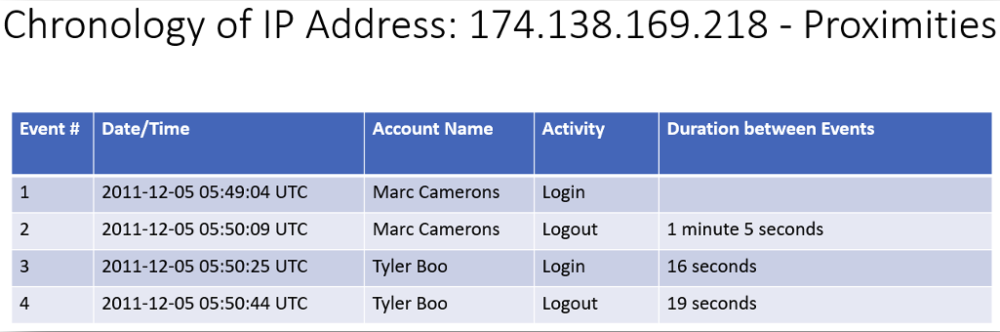

Where an IP Address was seen in multiple accounts and used close in time, I included that in a chart like this one:

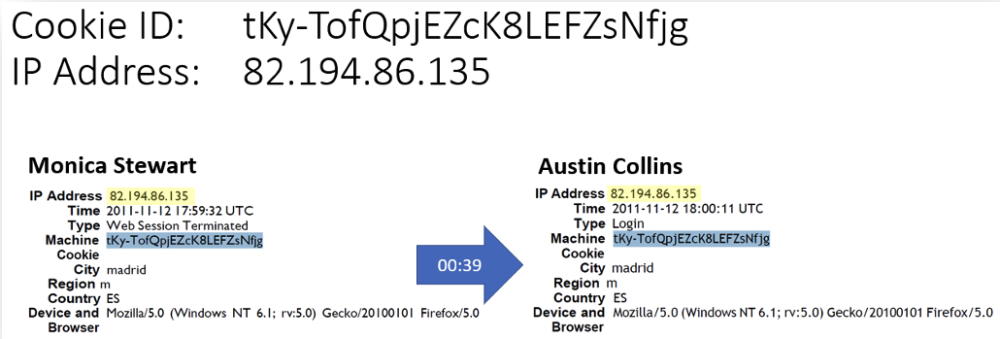

Machine Cookie ID and IP Address Example

I did not need to use YOSE for these ones because I had already documented them separately. These examples were created to show both artefacts in close proximity to one another using time and a chronological reference

The blue arrow and number inside of it showed the duration of time (seconds in this case) between activities in two different accounts. These accounts were accessed by the same device, browser, and Internet connection 39 seconds apart.

Each one of the aforementioned examples were prepared on a slide in PowerPoint as seen here. Some of these books were quite lengthy as a result of the common IPs, cookies, and the associated chronologies.

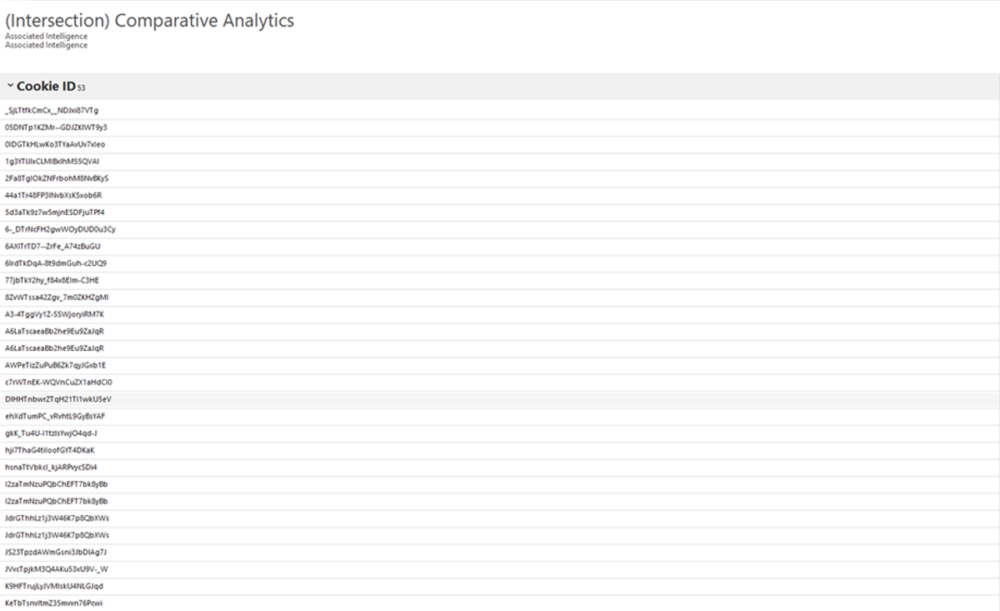

The final area YOSE assisted me with was in using the ‘Comparative Analytics’ feature. There were two accounts that had a lot of artefacts in common. They had a total of 171 unique machine cookie IDs combined. I needed to know how many of those intersected between the two accounts. YOSE showed me they shared 53 machine cookies, 46 of them were unique values.

Final Thoughts

My testimony and presentation to the jury was 4 days in duration. Defence successfully argued against allowing the jury to have any of my main reports about the technology or how it works. Instead, I had to give all of that testimony verbally or what is known as viva voce in legal terms. The jury were provided the “target” books for the 13 accounts I had prepared in a printed binder which was over 500 slides. We went through each book, and I was able to show them where there were connections between accounts. I provided my expert opinion on where these accounts were accessed from the same device and/or Internet service using the evidence I had prepared in conjunction with the Facebook records.

The information and examples I showed in this article were all a part of the public record and court proceeding. There are a number of media articles you could find via Google to read more on how the trial unfolded and the roles of the many experts who testified.

On August 6th, 2022, Aydin COBAN was convicted of all charges. On October 14th, 2022, he was sentenced to 13 years in prison. You can read the decision at this link.

This is not a story about me or what I did. I did what was asked of me and this is what we do as public servants. I had a duty to the court to analyze, explain, and provide opinion evidence about some data as well as how certain technologies work now and in the past. I know many officers both past and present capable of doing similar tasks if required. My role in this case was not to identify Aydin COBAN nor to say he was the one behind the Facebook accounts, I only connected the accounts to one person and device. There were many other investigators and experts from both Canada and the Netherlands, who each had a role in putting together the pieces of evidence necessary for the jury to reach a verdict.

The prosecutors did an outstanding job identifying the witnesses they required in order to facilitate calling complex technical evidence and presenting it in a way the jury could understand. The amount of preparation they undertook was practically immeasurable.

If you are an investigator reading this, YOSE does not have a “solve my case” button, no tool does. It can help with large volumes of structured data, and it can process data to provide intelligence or linkages between artefacts. It still requires analysis and more importantly authentication or confirmation of those links. I spent months putting all of these things together and drafting reports, you will need to make the same investment if someone calls on you in a case like this one.

Lessons to be learned here:

- Parents – talk with your kids, learn what they are doing online, and help them navigate a risky world.

- Social Media Companies – You are not doing enough, do better.

Despite my objective role in this case, as a former police officer, a father, a husband, and a human being I could not help but feel immense emotions for Amanda and her family. It took more than ten years for this case to close; I could not imagine what they felt.

Warren Bulmer

Warren Bulmer was a member of the Toronto Police Service for 30 years and in 2020 he retired from being a Detective Constable. Warren’s policing career has predominantly been spent within the field of criminal investigation. Since 2008, he has been an international instructor in computer- and Internet-facilitated crime, having lectured over 7,000 judges, prosecutors, and police from 39 different countries to date. Warren has taught at the United Nations in Bangkok, Thailand; the Canadian Police College; and the Ontario Police College and was a part-time faculty member at Humber College, where he instructed students in conducting online investigations and open-source intelligence techniques (OSINT). Warren has testified in court on many occasions as an expert witness in various capacities relating to digital evidence and computer forensic analysis as well as in the operation of social networks. He has also received awards for investigative excellence and holds a Police Exemplary Service Medal for his continuous public service. Since February 2020, he has been working for the Australian Federal Police in Brisbane, Queensland, as the Product Manager at the Australian Centre to Counter Child Exploitation. Warren also guest lectures in the University of Queensland’s Cyber Criminology undergraduate and graduate programs.

Get in touch!

Get actionable advice on how to solve more cases in less time with the Paliscope Platform. No strings attached!